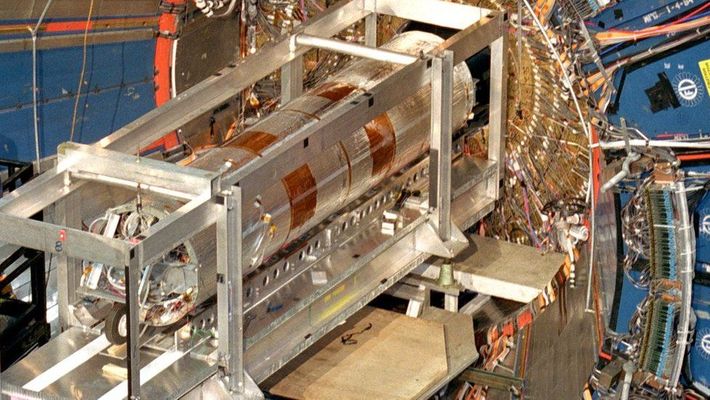

Scientists just outside Chicago have found that the mass of a sub-atomic particle is not what it should be. The amount is the first conclusive experimental outcome that is at odds with one of the most significant and successful theories of modern physics. The team has found that the particle, known as a W boson, is more enormous than the theories predicted. The outcome has been described as "shocking" by Prof David Toback, who is the project co-spokesperson. This innovation could lead to the development of a new, more complete theory of how the Universe works.

"If the results are confirmed by other experiments, the world is going to look different." he told. "There has to be a paradigm shift. The hope is that maybe this result is going to be the one that breaks the dam.

"The famous astronomer Carl Sagan said 'extraordinary claims need extraordinary evidence. We believe we have that."

- Machine finds tantalising hints of new physics

- Biggest cosmic mystery 'step closer' to solution

- Higgs factory a 'must for big physics'

The scientists at the Fermilab Collider Detector (CDF) in Illinois have found only a tiny difference in the mass of the W Boson compared with what the theory says it should be - just 0.1%. But if confirmed by other experiments, the implications are enormous. Until now, so-called Standard Model of particle physics has predicted the behaviour and properties of sub-atomic particles with no discrepancies whatsoever for fifty years.

CDF's other co-spokesperson, Prof Giorgio Chiarelli, from INFN Sezione di Pisa, said that the research team could scarcely believe their eyes when they saw the results.

"No-one was expecting this. We thought maybe we got something wrong." But the researchers have painstakingly gone through their results and tried to gaze for errors. They found none.

The result, published in the journal Science, could be related to hints from other experiments at Fermilab and the Large Hadron Collider at the Swiss-French border. These, as yet unconfirmed results, also propose deviations from the Standard Model, possibly as a result of an as yet undiscovered fifth force of nature at play.

Physicists have known for some time that the theory needs to be updated. It can't clarify the presence of invisible material in space, called Dark Matter, or the continued accelerating expansion of the Universe by a force called Dark Energy. Nor can it explain gravity.

Dr Mitesh Patel of Imperial College, who works at the LHC, believes that if the Fermilab result is confirmed, it could be the first of many new results that could herald the biggest shift in our understanding of the Universe since Einstein's theories of relativity more than a hundred years ago.

"The hope is that these cracks will turn into chasms and eventually we will see some spectacular signature that not only confirms that the Standard Model has broken down as a description of nature, but also provide us a new direction to support us understand what we are seeing and what the new physics theory looks like.

"If this holds, there have to be new particles and new forces to elucidate how to make these data consistent".

But the excitement in the physics community is tempered with a loud note of caution. Although the Fermilab result is the most precise measurement of the mass of the W boson to date, it is at odds with two of the next most accurate measurements from two separate experiments which are in line with the Standard Model.

"This will ruffle some feathers", states Prof Ben Allanach, a theoretical physicist at Cambridge University.

"We need to know what is going on with the measurement. The fact that we have two other experiments that agree with each other and the Standard Model and strongly disagree with this experiment is worrying to me".

All eyes are now on the Large Hadron Collider which is due to restart its experiments after a three-year upgrade. The hope is that these will deliver the results which will lay the foundations for a new more complete theory of physics.

"Most scientists will be a little bit cautious," states Dr Patel.

"We've been here before and been disappointed, but we are all secretly hoping that this is really it, and that in our lifetime we might see the kind of transformation that we have read about in history books."